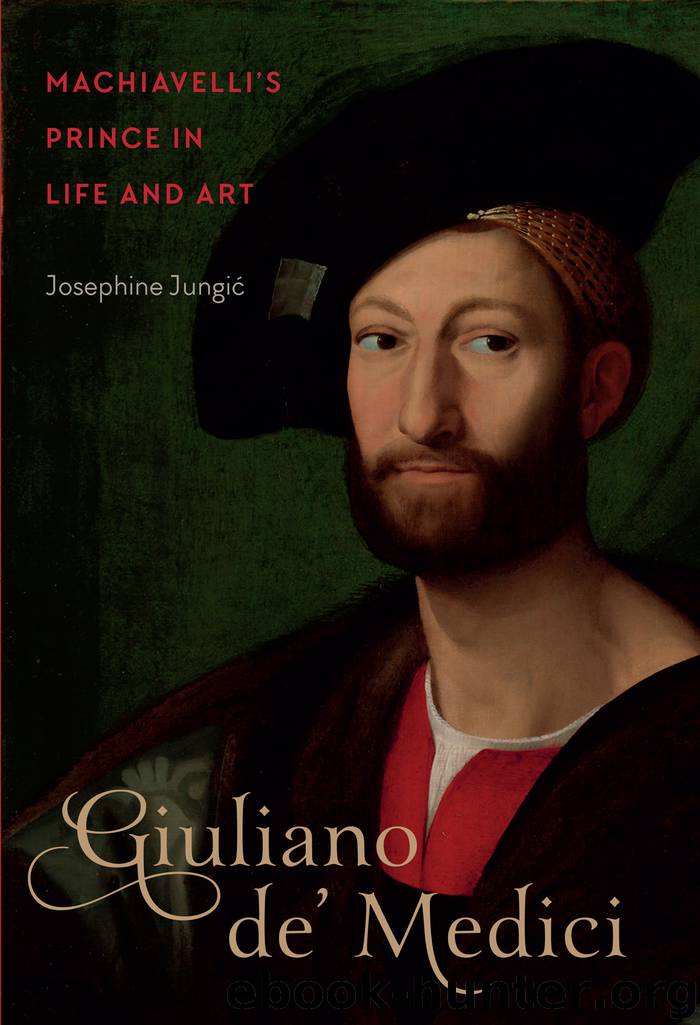

Giuliano de' Medici by Josephine Jungić

Author:Josephine Jungić

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: MQUP

Published: 2018-05-12T04:00:00+00:00

CHAPTER EIGHT

GIULIANO AS MACHIAVELLI’S IL PRINCIPE

The friendship between Giuliano de’ Medici and Niccolò Machiavelli, built upon a profound love of their native city of Florence and a shared passion for vernacular poetry, has already been discussed in previous chapters. Two eulogistic poems, argued in chapter 4 to have been composed in Imola in 1502, make apparent that the youngest son of Lorenzo the Magnificent made a profound impression on Machiavelli. In September 1512, as noted in chapter 1, it seems that Giuliano entrusted Machiavelli to write his “Letter to a Noblewoman” to Isabella d’Este in Mantua on his behalf. Indeed, there is every indication that Giuliano wanted Machiavelli to remain in his secretarial post in the chancery. As has been proposed in chapter 4, Machiavelli wrote his Ai Palleschi just before he was dismissed from government service in November 1512, as a warning to Giuliano not to listen to the advice given by radical palleschi. Soon thereafter, as one poet to another, Machiavelli sent two sonnets to Giuliano from prison in his hour of greatest need. Giuliano responded to Machiavelli’s pleas, so that, later, Machiavelli could write that he owed his life to the “Magnificent Giuliano.” Found innocent of conspiracy, he was set free despite those who still saw him as a dangerous enemy who had plotted against the Medici during his tenure as second chancellor of the Florentine republic.

In the last months of 1513, when he had to endure a forced idleness at his farm in Sant’Andrea in Percussina, Machiavelli wrote his famous, or infamous, as it came to be seen later in the sixteenth century, book The Prince.1 The work has generated a vast literature and an array of divergent and conflicting interpretations, not only regarding the book itself but also about Machiavelli’s political views. Two central questions have puzzled readers. First, what did Machiavelli intend to achieve by writing The Prince, and second, who was the presumed audience? Was it meant as a handbook to teach a new prince the rules of political power, including that evil deeds may have to be committed in order to acquire and maintain his new territories? Or was it a piece of disinterested political theory to prove to everyone, as Viroli contends, that even though he had been removed from office, his knowledge of the art of statecraft was unparalleled, and that he was a better political thinker than all the men of antiquity, particularly Cicero and his modern followers?2 Another great puzzle is that, in his Discourses on the First Ten Books of Titus Livy, composed at more or less the same time, Machiavelli spoke with the voice of a resolute republican, as he had in other writings, and adhered to a completely different political outlook and value system than that set out in The Prince. Described by Mansfield and Tarcov as a “decent and useful book,” the Discourses “advises citizens, leaders, reformers, and founders of republics on how to order them to preserve their liberty and avoid corruption.”3 How

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18605)

Red Sparrow by Jason Matthews(5452)

Harry Potter 02 & The Chamber Of Secrets (Illustrated) by J.K. Rowling(3659)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3526)

Drawing Cutting Edge Anatomy by Christopher Hart(3511)

Figure Drawing for Artists by Steve Huston(3431)

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Book 3) by J. K. Rowling(3340)

The Daily Stoic by Holiday Ryan & Hanselman Stephen(3287)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3155)

The Roots of Romanticism (Second Edition) by Berlin Isaiah Hardy Henry Gray John(2903)

Make Comics Like the Pros by Greg Pak(2900)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2867)

Draw-A-Saurus by James Silvani(2705)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (7) by J.K. Rowling(2703)

Tattoo Art by Doralba Picerno(2646)

On Photography by Susan Sontag(2622)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2569)

The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday & Stephen Hanselman(2562)

Drawing and Painting Birds by Tim Wootton(2494)